DPC Policy Note #18

Executive Summary

The question of the allocation of state and defense property in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) is again on the political agenda; a working group convened by the Office of the High Representative (OHR) is expected to continue its work until fall 2023. As the question of state property touches on corruption, environmental protection, local governance, and the nature of BiH as a state, understanding why it matters is important.

Background

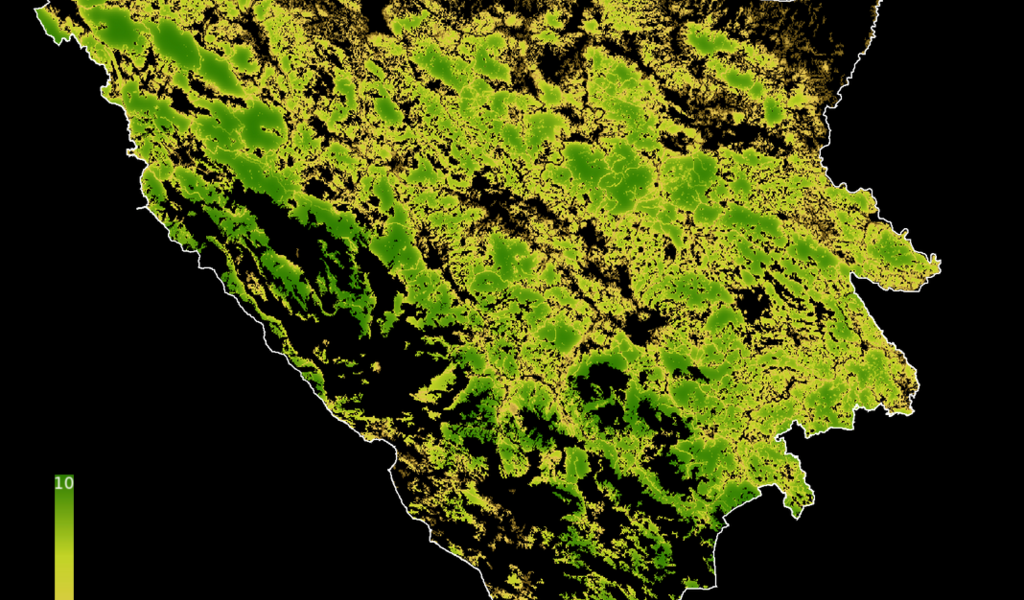

State and defense property refers to territory and objects that are currently owned by the state of BiH – an estimated 50% of the territory of the country. This includes property of the former Socialist Republic of BiH and property falling to BiH under the international succession agreement for the former Yugoslavia – immovable objects but also forests, agricultural land, rivers and other bodies of water, and the resources underneath the land, e.g., mines or yet untapped mineral deposits. The issue of who holds ownership over this property was not explicitly regulated in the Dayton constitution, but has come and gone as a policy priority over the years since.

In 2004, the Council of Ministers of BiH established a Commission for State Property; in 2009 an initial Inventory of State Property was established through the Office of the High Representative (OHR). In 2008, the Peace Implementation Council (PIC) included this issue within the “5+2” set of objectives and conditions for the closure of the OHR. In 2012, a decision from the BiH Constitutional Court clarified that the state of BiH is the sole owner of state property; two subsequent rulings in 2020 confirmed this decision. The issue is not mentioned in the EU Commission’s 2019 Avis which lists 14 priorities for opening accession negotiations.

State of Play

Since 2012, in line with Milorad Dodik’s efforts to weaken BiH and strengthen the entity of the Republika Srpska (RS) and reflecting the international community’s unmoored approach to BiH generally, the RS has ignored Constitutional Court rulings, instead illegally and non-transparently disposing of and selling off parts of state property. The issue is once again on the agenda for several reasons.

The key driving force is the critical state of RS public finances, as the entity needs assets and collateral to service past debt and incur additional debt. While most acute in the RS, the promise of new money is appealing to other domestic actors as well.

In addition, Croatia and Serbia, which have increasingly demonstrated their unfinished agendas towards BiH and their interest in a weak state (which would reduce resistance to external meddling), are poised to benefit handsomely from any property sell-off. So are other illiberal powers, both near (Hungary) and far (Russia, China).

The international community over the past several years has demonstrated increasing readiness to support and legitimize dealmaking by the ethnonationalist elites. The US wants to be able to further disengage by claiming Dayton loose ends are tied up. The EU wants to be able to claim that its “soft power” works and to justify the granting of candidacy post hoc, particularlysince Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is planning to visit the country in October. So there is a premium on signifiers of progress. All claim that beneficial foreign investment would result.

In 2021 Dodik suggested he could curtail his secessionist agenda if state property would be “resolved” to his liking. Rather than reacting to this as the blackmail it was, the European Commission picked up on his offer. In 2022, OHR convened an expert working group that is working in secrecy but is apparently assisting the Parliamentary Assembly in drafting a state law. The working group held its most recent session on July 14, 2023; it will likely continue into October. But the history of the issue suggests that there is no pressing need to try and resolve it now – in fact, the current political climate has produced the worst possible moment for doing so.

Why it Matters

Dodik insists on regulating the issue through an inter-entity agreement; this would feed his agenda of claiming that BiH is not a state but a sort of “state union.” He is therefore using this issue to try to redefine the nature of the state. This also suits Dragan Čović (HDZ BiH) and his backers in Zagreb, as they continue to try to carve out a Croat quasi-entity through “election law reform” and “Federation reform.” While any one of these state-weakening efforts is detrimental to BiH’s future, taken together they amount to dismantling the country. Some suggest that a state law would give the property rights to the level of municipalities. While this would appear to be in line with principles of decentralization, due to BiH’s structure – and the structure’s demonstrated incentives for malgovernance and obstacles to accountability – the long dominant verticals of power will continue to own and strip these assets for the benefits of the parties rather than the communities.

Dealing with this issue without addressing the theft to date would legitimize the corruption that has undergirded Dodik’s project.

Recommendations

1. A solution to the property issue – that is, property apportionment and disposition – should not proceed in the current, increasingly polarized environment. The international community – the EU, the US, the UK, and the other members of the PIC – should not let its priorities be dictated by Milorad Dodik or any of the other incumbents who have their eyes set on state property.

2. A fundamental reset of Western policy is needed to put an end to BiH’s unaccountable ethnocracy and to support development of a new social contract based on real devolution to local government, to finally replace the calcified partitocracy.

Only then should the property issue be tackled, in accordance with the following three principles:

• That it be a state law adopted by the BiH Parliament – not an inter-entity agreement as sought by Dodik;

• That in the division of property among governance layers, a large chunk of property must go to the state and to municipalities, with fail-safes in place to ensure municipalities benefit from these resources free from asset-stripping party agendas;

• That all illegal and unconstitutional (RS) property disposal decisions since the HR’s first disposal ban of state and defense property in 2005, in fact since 1995 – be annulled before any apportionment of the property among BiH’s different layers of government. Any other decision would mean legalizing theft, and irrevocably strangling the authority of the HR/OHR, the Constitutional Court of BiH and Court of BiH, and of the rule of law and constitutionality in general.